Irish Luck or Holy Trinity?

- msajaminor

- Mar 17, 2016

- 5 min read

The Kerry Patch is bound on the east by 16th street, the west by 22nd street, the north at Cass Avenue and the south, around O'Fallon St.,

with the heart of the neighborhood between 16th and 18th streets, Cass Avenue and O’Fallon St.

My grandmother (1924-2014) was extremely Irish Catholic. I think if she hadn't married my grandfather she would've been a nun. (But I also imagine that due to how cute they both were - if I do say so myself - they were probably irresistible to each other!) My grandparents grew up on the same street in the 20s, Cote Brilliante, where many Irish families had been fortunate blending into the St. Louis pot. I always wondered why my grandmother held so steadfast to her native religious heritage, like food and water, even though she grew up in St. Louis. I figure my great grandparents, who lived through squalor in their childhoods, had ingrained this into her and that they all attributed their blessings to a Higher Power.

Whatever it was, they 'started from the bottom.... Now I'm here'!

In the 1850s, after about 40 French speaking families took up residence in St. Louis and established the city, they began welcoming travelers from Kentucky, North Carolina, Tennessee and Virginia through the "gateway" on their way to the west. They were also joined by more English colonizers. Their settlement also included enslaved Indian and African residents.

Others moving west, and sometimes not moving along, were Germans, Southerners from South Carolina and Yankees and Republicans from New England, Ohio and Indiana. The pot was now seasoned with values of all different views.

The "Great Potato Famine", English oppression in their homeland and a chance for industrial opportunity in a burgeoning America brought millions of Irish immigrants in the 1800s. As the country began expanding, the Irish provided the labor needed for the construction of new cities and railroads. St. Louis, just as other large cities in America, had two separate mass migrations of Irish descendants. The first arrivals settled in the 5th Ward. They established boarding/rooming houses on Morgan Street (now Lacledes Landing) while they looked for work.

The red area is the 5th Ward. Many Irish also lived in the 4th ward (light blue). Source: Missouri History Museum

The second wave of poor, unskilled Irish were not as welcomed by the French, or even the "old Irish" that had already settled. They drank way too much (and in public!) for their religious taste and they felt they were ruining their reputation. They were humiliated when they started being compared to monkeys, a common insult also thrown to African Americans. The first priests in St. Louis were Irish, however, the religious division between the Protestant Irish and the Catholic Irish was also a source of angst within the Irish community.

Image Sources: "The Ignorant Vote...", Thomas Nast, Harper's Weekly,December 9, 1876, p. 985 & "And The Irish Became White", James Ford, www.patheos.com, MARCH 17, 2017

Things got violent on election day August 7, 1854, when street fights broke out at Second and Morgan Streets over Irish votes and accusations of bulldozing. An angry mob (considering themselves St. Louis Irish "natives") attacked the Irish as they fled into their boarding homes.

10 people were killed and 93 buildings were destroyed in a riot that lasted three days and resulted in better organization, uniforms and an increased number in the police force.

Image Sources: The Encyclopedia of the History of St. Louis, Vol IV, 1899 & ©2010 PHLMETROPOLIS.COM

The influx of Irish labor ended up decreasing the perceived necessity for slavery.

However, as slavery decreased, competition between the Irish and African Americans for low paying jobs became tense. Many Irish men found work in the clay-mines and breweries in South St. Louis.

John Mullanphy, a wealthy Irishman who made a fortune selling cotton in New Orleans, was able to maintain his stature in French St. Louis. He soon became a philanthropist, aiding poor Irish families and orphans in St. Louis, but most Irish banned together and formed communities for support. They settled in villages like the Kerry Patch, on the northside of St. Louis and in Cheltenham in the south.

And just as in many close living conditions where the need outweighs the resources, people did what they thought they needed to do to survive, even if this meant forming violent gangs - like they did back home under similar conditions - working the streets and hustling. Close to the river, the "Kerry Patch" grew notorious for prostitution, dog fighting and numbers rackets.

When Prohibition hit the city of breweries in 1920, the Irish were in business! With their homegrown brewing skills they were able to fight for control of the black market for liquor. Their barely habitable homes, or "shanties", were falling apart and the neighborhood was so dangerous, non-Irish St. Louisans were afraid they would be killed just passing through.

The St. Louis Register published this poem in the 1890s about the Irish culture there:

Duffy, I'm sorry the wife's feeling poor,

Play a soft tune, boys, when passing her door.

Fighting again, were ye, Danny, my b'y?

Who was it gave you the lovely black eye?

Thanks be to God for the brave Clan na Gael,

Johnny Bull trembles when you're out of jail!

-Emmet Kane

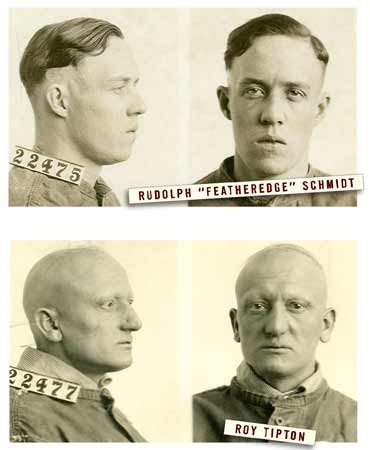

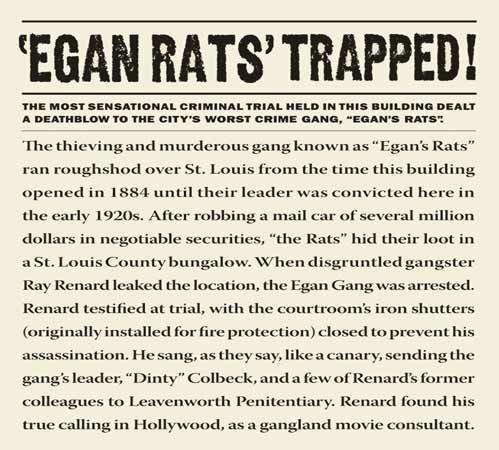

Within the Kerry Patch tenements and courtyards became infamous for high crime, like "Clabber Alley", "Castle Thunder" and "Wild Cat Chute". The violence in, what was known as the "Bloody Fourth" ward (and also known as "Bloody Third" & "Bloody Fifth" in headlines) was led by gangs such as Egan's Rats, the Red Hots, and the Cuckoos. The Robber's Roost and The Bucket Of Blood were popular saloons.

In Cheltenham, Irish worked in the clay mines and on the many new railroads being built downtown. Cheltenham is bound by Forest Park on the north, Macklind on the east, Manchester Avenue on the south, and Hampton Avenue on the west.

Cheltenham Post Office (Manchester Avenue just west of Hampton Avenue)

Image courtesy Missouri Historical Society

As the city grew, the religious Irish were able to climb out of poverty and move away from the sinful nature of the city by obtaining higher paying jobs like Wagner Electric until the start of the second world war. By the 1900s, they were moving West to neighborhoods near Cote Brilliante. Census records show this area was filled with Irish families, many of them doing well.

When the war ended and Charles Vatterott advertised his developing city in St. Ann with homes for families of 4, the Irish jumped at the chance to re-settle and build more churches and schools. (My grandparents also moved further west, from Page Avenue, in Overland, to next to Tiemeyer Park, in St. Ann, in the 1940s. My father, who was very young, delivered papers on his bicycle on that very busy street.) You can read the Irish descent in the names of these St. Ann neighborhoods.

Despite the many homeless and orphaned immigrants leaving and living in squalor upon arrival in America, many Irish families, including my own, were able to make it out of oppression and their descendants are now living the American dream!